Research Article

Research Article

The Art of Translation: Methods to Deal with the Cultural Connotations of Flower and Plant Names in the Chu Ci

Yichen Yang and Chuanmao Tian*

School of Foreign Studies, Yangtze University, China

Chuanmao Tian, School of Foreign Studies, Yangtze University, Jingzhou, Hubei 434023, China

Received Date: December 07, 2022; Published Date: December 16, 2022

Abstract

The Chu ci, the earliest anthology of Chinese romantic poetry by Qu Yuan and other poets, contains a large number of flower and plant names which have both referential and symbolic meanings. These meanings are so difficult to identify and determine today as to bring about great trouble in understanding and representing the names in translation. This article briefly explores the double meaning of some flower and plant names in the Li sao, the most important poem in the anthology, and examines the translation methods used in the English versions of the canon by Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang, David Hawkes, Xu Yuanchong, and Zhou Zhenying. The present study holds the philosophy of translation that any translating experiment is advisable in dealing with the names if their appropriate cultural connotations can be made clear.

Keywords: Chu ci, Flower and plant names, Cultural connotations, Translation methods

Introduction

The Chu ci (楚辞), or The Songs of the South, is an anthology of ancient Chinese poems by Qu Yuan and other poets which was produced during the Warring States period (5th century B.C.–221 B.C.) and the Han dynasty (202 B.C.–220 A.D.). “Chu” and “ci” in the title mean the “State of Chu” (one of the kingdoms of the Eastern Zhou dynasty) and “verse” or “song” respectively, and thus “Chu ci” means “verses of Chu” or “songs of Chu”. As the most important poet of the Chu ci, Qu Yuan was a loyal minister of the King Huai of Chu, but was banished by the latter due to the slanders of Qu’s rivals, and Qu created most of his great poems as a depressed loner in exile.

The Chu Ci and Its Plant Names

The anthology contains 17 poems according to The Verse and Chapter of the Chu ci (1985) by Wang Yi [1], the earliest, authoritative Chu ci commentator of the Eastern Han dynasty (see Table 1). Some of these poems are actually a collection of poems. For example, the Jiu ge consists of 11 pieces, including “Donghuang taiyi” (东皇太一, “The Great Unity, God of the Eastern Sky”), “Yunzhong jun” (云中 君, “The Lord Within the Cloud”), “Xiang jun” (湘君, “The Goddess of the Xiang”), “Xiang furen” (湘夫人, “The Lady of the Xiang”), “Da siming” (大司命, “The Great Master of Fate”), “Shao siming” (少司 命, “The Lesser Master of Fate”), “Dong jun” (东君, “The Lord of the East”), “He bo” (河伯, “The River Earl”), “Shan gui” (山鬼, “The Mountain Spirit”), “Guo shang” (国殇, “Hymn to the Fallen”), and “Li hun” (礼魂, “Honoring the Dead”).

As the first romantic anthology of poetry in Chinese literature, the Chu ci is characterized by strong local color, various gods and spirits, elegant language, rich imagination, and especially the poet’s love of his native country and his king, his hatred of evil-hearted courtiers, his worries of his motherland’s fate, and his sympathy for his countrymen’s miserable life. The anthology, together with the Shi jing (诗经, The Book of Songs), has an unrivaled place in Chinese culture and literature, exerting great influence on the creation of poems, novels, essays, and plays in later generations.

Table 1:Component parts of the Chu ci.

The Chu ci is notoriously known for the unintelligibility of its flower and plant names which are used to “symbolize virtue and ability” Watson [2]. The presence of symbolic or cultural connotations of these names is made very clear in Wang Yi’s frequently quoted words: “The Li sao is good at making allegory in that good birds and fragrant plants are used to represent loyal ministers, while evil birds and foul plants symbolize sycophants” (“善鸟香草, 以配忠贞; 恶禽臭物, 以比谗佞”). David Hawkes, Oxford University’s sinologist as the translator of the Ch’u Tz’u: The Songs of the South, points out two difficulties in translating flower names in the canon: Ch’u Tz’ŭ abounds in flower-names, and every translator of it is bound to devote a large part of his time to the problem of rendering them into English. The problem is twofold. In the first place many ancient Chinese flower-names are no longer identifiable with any certainty. In the second place, even when they are identifiable, the only available equivalent is often a jaw-cracking botanical name which no translator of any literary pretentions whatever could for a moment consider using Hawkes [3].

Arthur Waley, another British sinologist, reveals a third difficulty in dealing with various kinds of sweet-smelling plants in the source text (ST). He argues that, in ancient times, there was no systematic nomenclature based on structural differences, and one name often covered plants which had different meanings in different places and at different times Waley [4]. This is true of Chinese culture and other cultures. For example, in the nineteenth century, “cowslip” in Devonshire often meant foxglove; at Teignmouth people called buttercups “cowslips”; in North Devon, foxgloves were called poppies Friend [7].

Translaton Methods For Plant Names in the Chu Ci

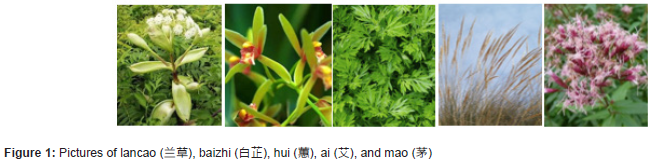

The Chu ci has been translated into quite a few Western languages, including English. In this article, we make a tentative study of the rendering of some flower and plant names in the Li Sao, the most important poem in the anthology and the longest poem in the history of Chinese literature which contains 187 lines, focusing on the cultural meanings of the names and the translation methods in the English versions of the Chinese classic by Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang [6], David Hawkes [3], Xu Yuanchong [7], and Zhuo Zhenying [8]. There are dozens of flowers and plants in the Li sao (see Table 2). Let us look at some examples in the specific verse lines in the poem.

Table 2:Plants in the Li sao and their translations.

Example 1:

Chinese original:

荃不查余之中情兮,反信谗而齌怒。 (Li sao, line 20)

English translations:

Xu: To my loyalty you’re unkind, oh!

You heed slander and burst in fire.

Yang & Yang: The prince my true integrity defamed,

Gave ear to slander, high his anger flamed;

Zhuo: The Calamus ignored my holy sentiment

And, credulous to slander, his spite he did vent.

Hawkes: But the Fragrant One refused to examine my

true feelings:

He lent ear instead to slander, and raged against me.

“荃” (quan) in example 1, also called “荪” (sun), is a type of fragrant grass and grows near water, and here it is metaphorically used to refer to the King Huai of Chu Wang [1]. Only Zhuo retains the plant image and translates it into “the Calamus”; Xu, the Yangs, and Hawkes freely render it as “you”, “the prince”, and “the Fragrant One” respectively. Zhou’s rendering fails to clarify the symbolic meaning of “荃”, even though he capitalizes the first letter of “calamus” and thus implies that it has a special meaning. A note like Hawkes’ can facilitate target readers’ understanding: “Fragrant One: the Chinese word quan, literally a kind of iris or flowering rush, is used here by the poet in addressing his king” Hawkes[3]. Xu’s and the Yangs’ translations omit the plant and replace it with a personal pronoun “you” and the noun phrase “the prince” respectively. They are acceptable because they can easily remind the readers of the King Huai.

Example 2:

Chinese original:

兰芷变而不芳兮,荃蕙化而为茅;

何昔日之芳草兮,今直为萧艾也。 (Li sao, lines 155-156)

English translations:

Xu: Sweet orchids have lost their fragrant smell, oh!

Sweet grass turn to weeds stinking strong.

…Turn to weeds and wormwood unfair?

Yang & Yang: E’en Orchids changed, their Fragrance quickly

lost,

And midst the Weeds Angelicas were tossed.

…Their Hues have changed, and turned to Mugworts grey?

Zhuo: The Orchid and Angelica lose their perfume.

And the form of Wild-Grass the Magnolia does assume.

…To the status of such grasses as the Moxa which stink?

Hawkes: Orchid and iris have lost all their fragrance;

Flag and melilotus have changed into straw.

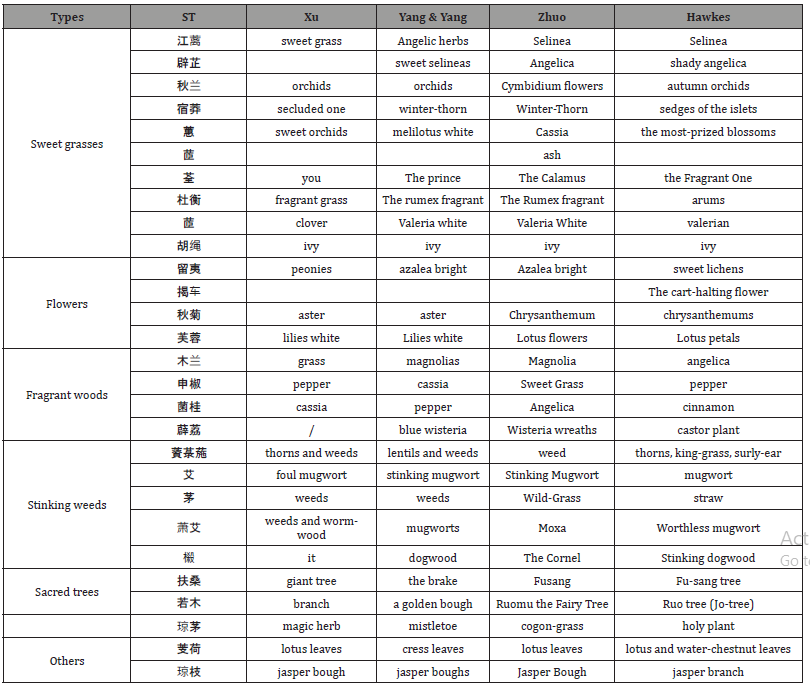

…Now all transformed themselves into worthless mugwort? The plants such as “兰” (lan), “芷” (zhi), “荃”, and “蕙” (hui) mentioned in example 2 are fragrant plants with some medicinal value, which represent the lofty character and cultivated personality in the ST Wang [1] (see Figure 1). On the other hand, “茅” (mao) and “萧艾” (xiao ai) represent the evil character. This example implies that the King Huai of Chu favors his ministers of calumny, which is a kind of metonymy for political relationship. Generally speaking, we have to do research on the botanical meaning of the plants and figure out their cultural contextual meanings. In example 2, “兰芷” is translated respectively as “sweet orchids”, “orchids”, “orchid and angelica”, and “orchid and iris”. Xu and the Yangs see “兰芷” as one plant and translate it into “orchids”. But Xu adds the adjective “sweet” to modify “orchids”’, reproducing the characteristic of the plant. Zhuo and Hawkes think of it as referring to two plants, but they do not have the same understanding of “芷” in that they render it as “angelica” and “iris” respectively (see Figure 2). According to Wang Yi [1], “兰” is a kind of sweet grass living in secluded places, and here it alludes to the younger brother of the King Huai because his name “Zi Lan” (子兰) contains the character “Lan” (兰). According to the poem, Zi Lan was righteous at the beginning but became sinful later due to the effects of some evil-hearted courtiers. “芷” in the poem refers to several fragrant plants in different contexts, such as “chai” (茝), “ruo” (若), or “heng” (蘅), and its referential meaning cannot be determined today. Therefore, all the translations can be acceptable, and Zhuo’s and Hawkes’ renderings are a little better. As for the rendering of “茅”, Hawkes reproduces it with the word “straw” which is an agricultural by-product that is not the plant the ST refers to. Both Zhuo and Hawkes adopt the interpretation method and translate the plant “艾” into “moxa which stink” and “worthless mugwort” respectively. By adding the verb “stink” and the adjective “worthless”, the characteristics of the two plants are conveyed accurately. The poet uses “茅” and “艾” to refer to crafty sycophants around the King Huai, which constitutes a sharp contrast to the commendatory meanings of “兰芷” and “荃蕙”. Use of notes to clarify the symbolic meanings of these plants can help target readers better understand the poem.

Example 3:,/

Original Chinese:

总余辔乎扶桑。折若木以拂日兮 (Li sao, line 98)

English translations:

Xu: I tie their reins to giant tree.

I break a branch to brush Sun’s path, oh!

Yang & Yang: Where bathed the sun, whilst I upon the brake

Fastened my reins; a golden bough I sought

Zhuo: Which I tie to Fusang, ’neath which the sun does outburst.

I break off a branch from Ruomu the Fairy Tree

Hawkes: And tied their reins up to the Fu-sang tree.

I broke a sprig of the Ruo tree to strike the sun with

In example 3, both “扶桑” (fu sang) and “若木” (ruo mu) are legendary trees that relate to the sun, and the relevance between the trees and the sun must be reflected in the translation. Hong Xingzu, another famous Chu ci commentator of the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127), offers the description of the trees in the Tales of Ten States as follows: “Fusang trees grow in blue seas; the leaves are like those of white mulberry; they are as long as thousands of meters and as wide as two thousand meters; they tend to grow in twos; they are called Fusang” (“扶桑在碧海中, 叶似桑树, 长数千 丈, 大二千围, 两两更相依倚, 是名扶桑”) Hong [9]. This shows that “扶桑” is also called “大木” (big tree). Xu’s translation of “giant tree” may enable target readers to realize how magic the tree is. The Yangs replace the tree with the word “brake”, which not only omits the original culture but also fails to convey the connotation of the plant. It can be argued that, without the contextual knowledge about the tree “扶桑” in Chinese culture, the target readers may have to make great effort to get the associative meaning in the Yangs’ version. On the contrary, Zhuo adopts transliteration and interprets it as “Fusang, ’neath which the sun does out burst” which not only retains the original cultural image, but also discloses the relationship between “扶桑” and the sun. Hawkes’ version helps the readers grasp the original meaning with a note like this: “Fu-sang tree: Mythical tree in the far east which the sun climbs up in his rising. According to one version of the myth, it had ten suns in its branches, one for every day of the week” Hawkes [3].

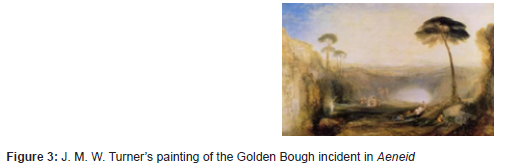

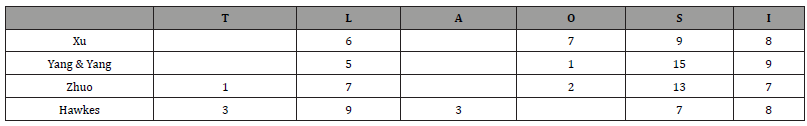

“若木” is another name of “扶桑”, which also relates to the sun Wang Yi [1]. Xu roughly translates it as “branch” which is unable to convey the associative meaning of the plant. The Yangs make a wrong assumption and interpret “若木” as “golden bough” which may somewhat remind the readers of the scene that the sun is shining over the tree. However, in the West, “golden bough” is reminiscent of J. M. W. Turner’s painting (see Figure 3). Meanwhile, “golden bough” is also existent in the Latin epic poem The Aeneid by Virgil between 29 B.C. and 19 B.C., in which Aeneas and the Sibyl present the golden bough to the gatekeeper of Hades to gain admission Butlin and Joll [10]. In Roman mythology, “golden bough” has nothing to do with the sun, which gives rise to the cultural dislocation and fails to represent the original meaning. According to the data analysis, the frequency of the translation methods used by the translators to translate the plant images in the Li sao is obtained based on the statistic results (see Table 3). The data in Table 3 clearly shows that it is the method of substitution that the translators use most frequently when translating the plants, while transliteration and annotation are seldom used. Xu tends to replace the plant names with general terms. For example, he translates “江 蓠” (jiang li) and “辟芷” (pi zhi) as “sweet grass”, “杜衡” (du heng) as “fragrant grass”, and “茅” as “weeds”. On the one hand, this kind of rendering is easy to understand; on the other, the target readers will find it difficult to know the specific referential meanings of the plants.

Table 3:Translation methods for plants in the Li sao.

Note: T=transliteration, L=literal translation, A=annotation, O=omission, S=substitution, I=interpretation

Concluding Remarks

It is no doubt that all Chinese and foreign translators will encounter great difficulties in rendering flower and plant names in the Chu ci, and thus any translating experiment is welcome in this regard. Only when translators get a thorough understanding of the names through an extensive reading and an in-depth study of all important Chu ci commentaries in Chinese history will they not get lost in translation when dealing with “the murky allegory that pervades many passages” in the canon Watson [2].

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Wang Yi (1985) The Verse and Chapter of the Chu ci. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing.

- Watson Burton (1962) Early Chinese Literature. Columbia University Press, New York, and London.

- Hawkes David (1959) Ch’u Tz’u: The Songs of the South–An Ancient Chinese Anthology of Poems by Qu Yuan (Eds.), and Other Poets. Clarendon, Oxford, England.

- Waley Arthur (1955) The Nine Songs. A Study of Shamanism in Ancient China. Allen & Unwin, London.

- Friend Hilderic (1884) Flowers and Flower Lore. W. S. Sonnenschein, London.

- Yang Xianyi, Gladys Yang (1953) The Li Sao and Other Poems of Ch’ü Yüan (Selected Elegies of the State of Chu). Foreign Language Press, Beijing.

- Xu Yuanchong (1994) Elegies of the South. China Foreign Translation and Publishing Corporation, Beijing.

- Zhuo Zhenying (2006) The Verse of Chu. Hunan People’s Publishing House, Changsha.

- Hong Xingzu (1983) Some Additions to the Chu ci. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing.

- Butlin M, Joll E (1977) The Paintings of J M W Turner. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

-

Yichen Yang and Chuanmao Tian*. The Art of Translation: Methods to Deal with the Cultural Connotations of Flower and Plant Names in the Chu Ci. Sci J Research & Rev. 3(3): 2022. SJRR.MS.ID.000564.

Anthology, Sweet-smelling plants, Cowslip, Chinese literature, Giant tree

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.